January 23rd Both the Russian opposition and the authorities are preparing for Saturday’s protests. Here’s what you need to know.

Sergey Savostyanov / TASS

To get you up to speed

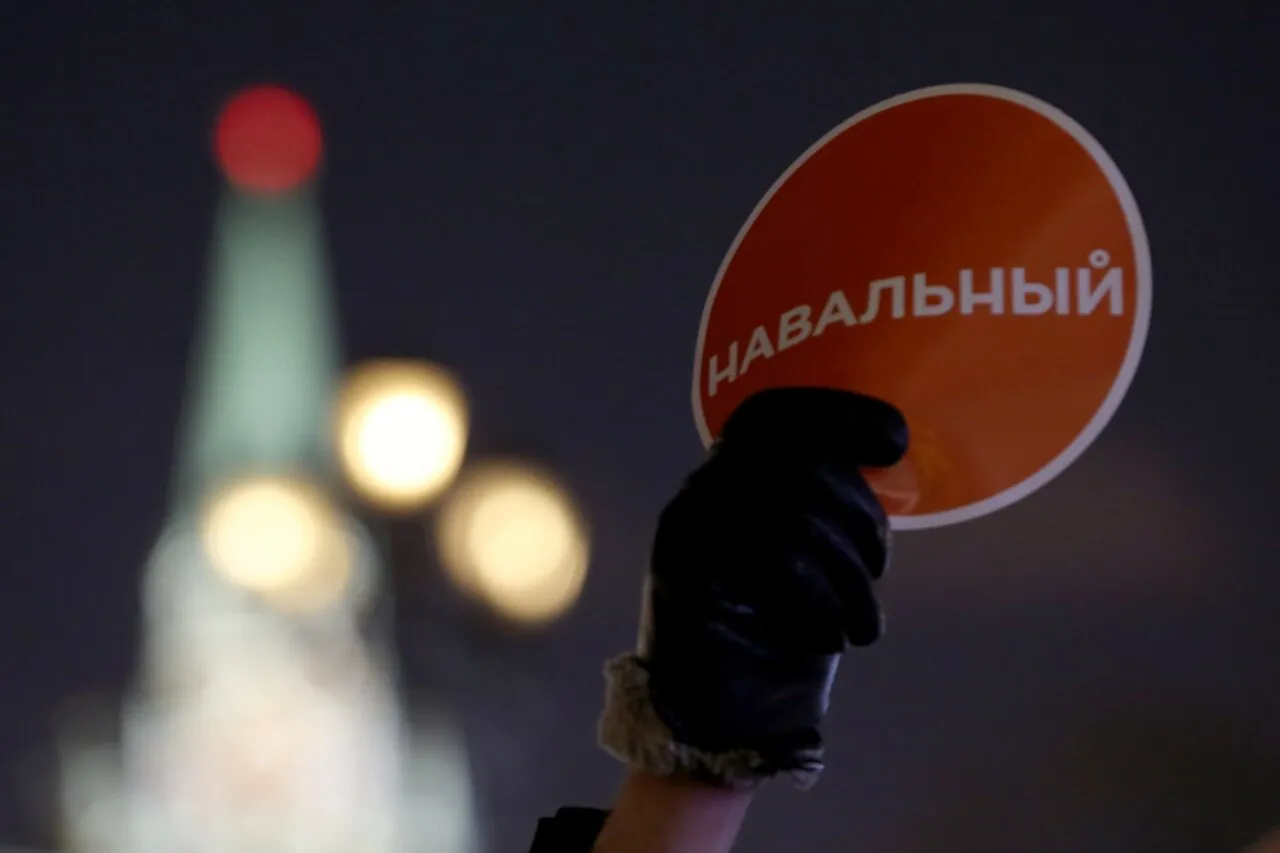

On January 18, Russian opposition figure Alexey Navalny released a video message calling on his supporters to take to the streets. This came after he was remanded in custody for 30 days during a hearing inside a police station in Khimki (a town near Moscow). Immediately after Navalny’s video went online, an event appeared on Facebook under the slogan “Freedom for Navalny!” — it announced a rally set to take place in Moscow’s Pushkin Square beginning at 2:00 p.m. local time on Saturday, January 23.

Navalny was remanded in custody at the request of Russia’s Federal Penitentiary Service in connection with a complaint the department filed against him for allegedly violating the terms of his probation in the Yves Rocher case. The prison authorities are now seeking to revoke Navalny’s probation (which technically ended on December 30, 2020) and incarcerate him under a reinstated 3.5-year prison sentence.

The Yves Rocher case dates back to 2014, when Alexey Navalny and his brother Oleg were found guilty of embezzling funds from two Russian companies associated with the French beauty and cosmetics brand “Yves Rocher.”Oleg Navalny was sentenced to 3.5 years in prison and Alexey Navalny was given a 3.5-year probation sentence. The brothers pleaded not guilty, calling the case politically motivated.

In 2017, the European Court of Human Rights declared the verdicts “unjust” and ordered the Russian authorities to pay the Navalny brothers compensation. Their sentences were never overturned, however.

Russia’s prison authorities maintain that Navalny violated his probation during his stay in Germany, where he spent nearly five months recovering from chemical nerve agent poisoning.

The organizers behind the rally — Navalny’s team headquarters in Moscow — described its aims as follows:

Vladimir Putin is so afraid of Alexey [Navalny] and all of us that he’s prepared to violate all laws to jail him for many years. We must not let this happen! So, on January 23, the entire country is going to come out in support of Alexey Navalny. We are against political repression and we are against violations of the laws of our country.

Navalny’s supporters in other regions joined in and began organizing similar protests (Team Navalny’s Telegram channel and Facebook page both have detailed lists of all the cities where rallies are scheduled to take place).

At the time of this writing, Team Navalny’s list includes planned rallies in more than 65 cities and towns across the country; protests are set to happen in every Russian city with a population of more than one million people.

Interest in the rallies skyrocketed after Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation published a major investigation into billion-dollar “palace” on the Black Sea supposedly built for President Vladimir Putin. The video version of the investigation, which was released on YouTube, racked up more than 50 million views in two days (it also includes a call to take to the streets in support of Navalny on January 23).

Many well-known figures in Russia have publicly demanded Navalny’s release and some have even repeated calls to protest his detention. Many consider his persecution illegal and politically motivated. Amnesty International declared him a prisoner of conscience immediately after his arrest.

Are these rallies authorized by the authorities?

No. Navalny’s supporters (with rare exceptions) haven’t mentioned plans to get official permission from the authorities to hold rallies on January 23.

Team Navalny’s St. Petersburg headquarters, for example, decided there was no point in even trying. “Alexey [Navalny] was detained at the airport, then he ended up at a trial absolutely illegally. In this situation, demanding that we act in accordance with the law when the authorities will refuse us once again is very strange,” said the head of his regional team office, Irina Fatyanova.

Oleg Stepanov, the head of Team Navalny’s Moscow headquarters, said that protesters will be taking to the streets without official approval because “the fate [of an application to hold a rally] is known in advance.”

In any case, getting permission to hold a rally in such a short time period is physically impossible: by law, an application for a rally must be submitted to the local authorities for approval no earlier than 15 days and no later than 10 days before the day of the event in question.

Nevertheless, some activists tried to get permission to hold small pickets (notices for this type of gathering have to be submitted three days in advance). The local authorities refused, citing coronavirus restrictions. This is exactly what happened in the Siberian city of Irkutsk.

Are the authorities trying to stop the protests?

Yes. On Thursday, January 21, the Russian Attorney General’s office announced a “prosecutorial response” in connection with the “calls for participation in illegal mass events on January 23, 2021.” In particular, it ordered Russia’s state censorship agency, Roskomnadzor, to restrict access to online content featuring these “calls.”

In turn, Roskomnadzor ordered TikTok and VKontakte to protect minors from “calls to participate in protests” and threatened to fine social networks (including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Youtube, as well) for failing to comply with its requirements (namely, removing content deemed illegal).

“Individuals calling for illegal actions have been warned about the inadmissibility of breaking the law,” the Attorney General’s Office added — apparently referring to the official warnings that police officers and state prosecutors issued to many of Navalny’s regional associates on January 20 and 21. Opposition figure Lyubov Sobol, who works for Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, was among the people who received one of these “warnings.”

At the same time, police officials promised that the “agitators behind the unauthorized protests on January 23” — which, in their words, are being organized by “some quasi-politicians” — would be held accountable even before the rallies take place. The police then proceeded to make good on this threat. For example, they charged the coordinator of Team Navalny’s Omsk office, Olga Kartavtseva, with an administrative violation for announcing a rally on social media (a court later fined her about $270). Similar charges were also drawn up against Lyubov Sobol. After that, Moscow police began arresting Navalny’s closest associates.

Universities across the country are also calling on students not to attend the rallies. Some institutions are even threatening to expel students who take part in the demonstrations (at the Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation in Moscow, the head of the management faculty issued such a warning to students, though the university administration later said that this isn’t official policy). Reportedly, some universities are drawing up lists of students who belong to pro-Navalny groups. And in some parts of the country, students are expected to attend classes this upcoming Saturday.

In some regions, the administrators of schools appear to be taking action, as well. Parents of schoolchildren in Perm were informed that administrators intend to register kids who take part in unauthorized rallies with the Committee for Juvenile Affairs. Parents of schoolchildren in Kazan and St. Petersburg received similar warnings.

What if I want to attend a rally anyway?

If you can read Russian, check out Meduza’s articles on what you can and cannot do at protests in Russia, what to do if you or a friend are detained by the authorities (as well as possible charges you may face), and how to seek compensation for illegal detention.

Also, keep in mind that at the end of 2020, Russian lawmakers tightened a wide variety of legislation, including the rules governing participation in demonstrations. One new law stipulates punishments of up to a year in prison for blocking roadways, if this action threatens citizens or “creates a threat” of destruction or damage to property. In addition, journalists governing protests have been banned from direct participation in rallies (for example, they can’t carry signs or hand out leaflets).

What about the coronavirus?

Unfortunately, it’s hard to give good advice on this question. It is possible to transmit or contract the coronavirus while outdoors, though it’s less likely than when you’re indoors. The World Health Organization (WHO) advises maintaining one meter (3 feet) of social distance at the very least (but as a rule it’s best to stay as far away from other people as possible). And you definitely shouldn’t attend a public gathering if you have a cold or other COVID-19 symptoms, or you have recently come in contact with a coronavirus patient.

Although having your face covered while at a public gathering is prohibited in Russia, wearing a mask is recommended for preventing the spread of COVID-19. In a comment to Meduza, lawyer Alexander Peredruk from the rights organization “Apologia Protesta” explained that the “ban” on covering your face isn’t a hard and fast rule — even if you’re attending an unauthorized rally. Russia’s Constitutional Court has emphasized that this rule doesn’t prevent the use of masks or other face coverings due to inclement weather or for medical reasons, he says. In other words, you can only be charged if you’re explicitly trying to hide your identity. The way Peredruk sees it, in the context of the coronavirus pandemic “wearing a mask can be considered not only not prohibited, but also desirable.”

What will ‘Meduza’ be doing on Saturday?

Meduza will be covering the protests all day long. Our photographers and correspondents will be working in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other major cities across Russia. For faster updates in English, you can follow us on Twitter.

Text by Pyotr Lokhov with additional reporting by Daria Sarkisyan, Irina Kravtsova, and Sultan Suleimanov

Translated and abridged by Eilish Hart