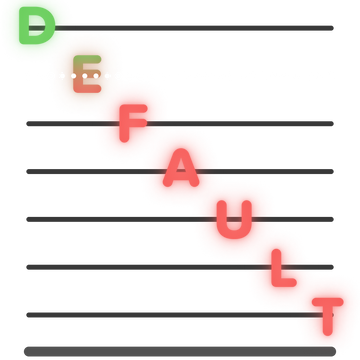

Russia’s debt default What the 2022 financial crisis will mean for the country and its people

What happened?

“Russia has defaulted on its foreign-currency sovereign debt for the first time in a century,” Bloomberg reported on Monday, June 27.

The technical default occurred at the end of day on Sunday, when the grace period for paying $100 million on two eurobond coupons expired. According to Bloomberg, Russia missing this deadline is “the culmination of ever-tougher Western sanctions that shut down payment routes to overseas creditors.”

Meduza asked economist Ruben Enikolopov to explain what this means for the country as a whole and for Russians individually.

Please note. Meduza first published this explainer back in March 2022, when Moody’s Investors Service downgraded its long-term debt rating for the Russian government and forecast that it would not be able to make the next payment on its external debt. This article was updated on June 27, after the technical default occurred.

Will the default affect Russia right away?

No, it won’t. Experts who spoke to Bloomberg noted that Russia’s default is unique in that it is mostly symbolic (for the time being). The Russian government has the reserves to cover debt obligations, but is technically unable to make the payments. Earlier, Russia’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanov insisted that “this is not a default at all,” dismissing the situation as “farce.”

The default comes after the US Treasury closed a sanctions loophole by deciding not to extend the validity of an exemption that allowed Russia to service its foreign debt in dollars. In turn, Russia began to make payments in rubles. However, due to sanctions, the funds did not reach international creditors.

Major ratings firms would typically be the ones to formally declare an “event of default,” but they withdrew ratings on Russian entities after Moscow began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Bondholders could also file a claim against the Russian government seeking urgent repayment. However, Siluanov made clear that Russia does not consider itself responsible for the “artificial barriers” preventing it from transferring payments.

Is this a default like in 1998? With a total collapse afterwards?

The differences between then and now are significant.

In 1998, the default was the start of the crisis (though the problems that caused it had been accumulating for a long time). In 2022, however, it’s just one of many signs of the difficult situation in which the Russian economy finds itself. An important distinction is that the 1998 default directly and primarily affected banks that had purchased government short-term bonds (GKOs) for which the state then stopped making payments. Today, the first to suffer will be foreign borrowers who bought federal loan bonds (OFZs).

Is this because of the sanctions?

In part.

Russia’s ability to pay off its debts is limited by the fact that the Central Bank’s foreign exchange reserves, which were earmarked for this purpose, have been frozen. Analysts compare Russia’s current position to the situation in which Venezuela found itself on the eve of its default in 2017. In both cases, the value of public debt fell close to zero (meaning that no one wanted to buy the government’s obligations). Additionally, Venezuela’s main export industry — oil — was then under sanctions. Were it not for this, the country would have been able to pay off its debts.

Technically speaking, if it wanted, the Russian leadership could agree to unfreeze part of the Central Bank’s reserves specifically to pay off the country’s external debt, but Moscow has instead signaled that it has no wish to pay these debts.

So, Russia is allowing itself to go into default?

Yes.

In particular, the government has issued special decrees stating that payments to entities in “unfriendly” countries (this list includes virtually all the world’s developed nations) can be made in rubles. Foreign creditors view this as a default because rubles are now of little value, and they cannot exchange rubles for a foreign currency and withdraw it from Russia. In fact, these new decrees violate Russia’s contractual obligations insofar as the agreements for these debt securities stipulate that payments must be made in a foreign currency.

This is the difference between public and corporate debt. In some cases, the latter can be paid in rubles in Russia, but it’s stated clearly with public debt in which currency it must be repaid. Russia’s refusal to abide by these terms will be a violation of its obligations, constituting a default.

Will ordinary Russians suffer because of this?

At first, the default won’t affect the general public, at least not directly. Indirectly, though, everyone will feel its effects.

After the default, any foreign investment will cease for a very long time because the Russian economy will be viewed as extremely high risk. In the best case, even if the sanctions are lifted, borrowing will become extremely expensive for both the Russian state and Russian companies.

These developments also completely squander the country’s macroeconomic stability, which has been taking shape for many years. We could witness sharp rises in inflation and unemployment, the contraction of the entire economy, and a decline in people’s well-being. And it’s unknown how long it will take to make up all this lost ground.

Text by Ruben Enikolopov

Translation by Kevin Rothrock