‘I heard them screaming’ In hiding abroad and awaiting her sons’ sentencing, the mother of two detained Chechen activists tells her family’s story, in her own words

In February 2021, 17-year-old Ismail Isayev and 20-year-old Salekh Magamadov were kidnapped by the Chechen authorities and taken from Nizhny Novgorod to Chechnya. According to the two brothers, the authorities subjected them to violence and threats until they agreed to waive their right to legal counsel and confess to being involved in an illegal armed group; investigators accused the brothers of smuggling groceries to Chechen militant Rustam Borchashvili when he was in hiding. Isayev and Magamadov are slated to be sentenced later this week and are facing years behind bars. The brothers’ lawyers insist the case is politically motivated. In fact, Isayev and Magamadov were previously detained on suspicion of running an opposition Telegram channel. What’s more, one of the brothers is gay and the other is transgender, which puts them at even greater risk of persecution in Chechnya. A petition demanding their release has gathered more than 100,000 signatures so far. The boys’ mother, Zara Magamadova, who is currently in hiding from both the Chechen and federal authorities, also maintains her sons’ innocence. For Meduza, Zara Magamadova tells her family’s harrowing story, in her own words.

Please note. This article was first published in Russian on February 4, 2022.

We were a regular family. I’m from Goity, a village [located about 12 kilometers, or 7.5 miles from Grozny]. I’m 50 years old. I got married 24 years ago. My husband lived in the village of Michurina — he grew up there. So I went to him. When you get married, it doesn’t matter what the place is, [you move there]. After the second [Chechen] war, we lived in the ruins of a house with my husband’s mother, we only had one room.

I have three children, three sons — Said, the eldest, Salekh, and Ismail. I used to work in the market. My husband helped me and built our home. And the kids helped him and went to school. They finished the ninth grade, then they enrolled in college in Grozny. They studied programming. They wanted to be developers. And that was our life. There was nothing out of the ordinary.

My kids were always so calm, without a care in the world. Even when they were sick, they wouldn’t cry. Salekh is still just as calm, peaceful. He’s always studied languages: first Japanese, then French, I think. He always wanted to study. Ismail didn’t do anything — he went to karate lessons when he was little, but then he changed his mind. Ismail’s personality is such that he could always speak his mind and communicate with everyone. I spent all day at work — from morning to evening. So I only saw them in the evenings. We didn’t really manage to talk much; I was working every day.

‘I thought if they didn’t go out, everything would be okay’

In August 2019, I got a call from the police station that Ismail had gotten into a fight with someone, gotten detained, and I should “come down.” What had actually happened was that they [the police] had been checking [people’s] phones on the street and probably stumbled upon him. There wasn’t anything on it, but there was a [LGBTQ+ pride] flag. Ismail told me later that it was for no reason, just for kicks. Making excuses, probably.

They held Ismail for about eight days, until we paid 300,000 rubles [nearly $4,000] for [his release]. Relatives gave us a little money, and their grandmother said, “Give them my whole pension to get my grandson back.” She was prepared to do anything. We didn’t tell anyone what exactly he had been detained for. But they were detaining everybody there [in Chechnya]. And our relatives knew they could detain anyone they wanted just for liking something [on social media].

[The kidnappings in Chechnya began] many years ago. There were a lot of rumors — they took this person, they took that person. Lately, I’d even say it’s become commonplace. There were [cases of kidnapping] in our village, too, but I didn’t know the people personally. To be honest, I didn’t think this could happen [to my children too]. They didn’t have any close friends, they always stayed at home, helping around the house. So I didn’t think this would affect us. I thought that if they stayed at home, this wouldn’t reach us. I thought that if they didn’t go out, didn’t talk to anyone, everything would be okay.

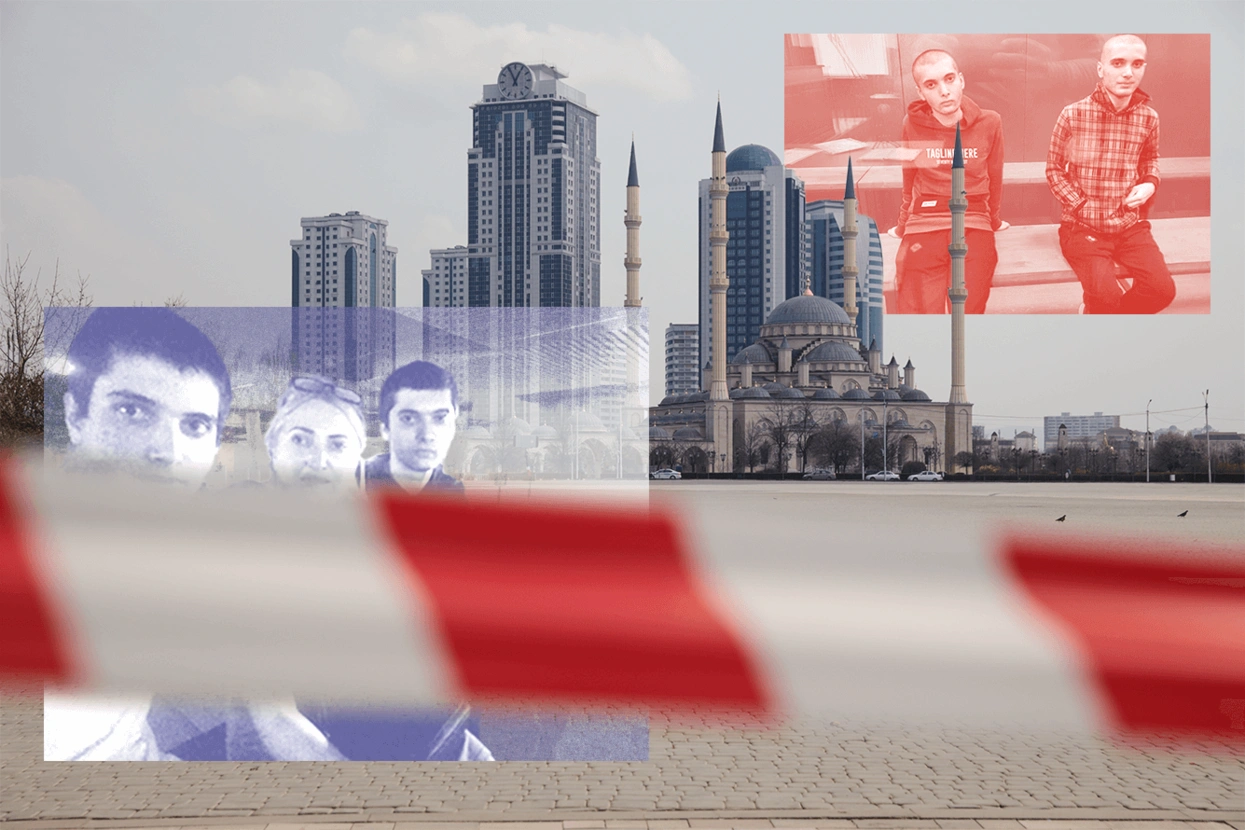

Zara Magamadova with her sons Ismail Isayev and Salekh Magamadov

Zara Magamadova’s personal archive

After three or four months, Ismail went to St. Petersburg. He said he wanted to work and that he would go to school there. I agreed, I thought he would just be there for a month, to have some fun. Then Ismail called me one day and said he was going to the pharmacy. This was in April 2020, when quarantine was strict. An hour went by, I got worried, so I called him. He picked up the phone and said he was in a friend’s apartment, the friend had gone out, and he was playing some kind of games on the computer. That struck me as really strange. I tried calling him again, but he stopped picking up the phone.

After thirty minutes or an hour, the police showed up [at our home in Michurina]. Without explaining anything they detained everyone and took us to the Akhmat Hadji Kadyrov Regiment [Chechnya's notorious police patrol service regiment]. There, they took me down to the basement, where they handcuffed me to a Swedish ladder. At the same time, they were torturing my sons [Said and Salekh]… I heard them screaming. I was terrified, it was really scary. I prayed for them and refused to believe what was happening. I didn’t know what to do, I just sat on the floor. Sometimes the police would come in and hit a pipe against the bars or against the ground to scare me. They didn’t explain anything, they just threatened me, saying they could beat me whenever they wanted. They brought me buckwheat and tea, but I didn’t eat anything. I only drank the tea because I was thirsty. They didn’t bring [my oldest son] Said anything but tea and a cookie.

The next day, they brought Ismail [to the regiment]. We — Said, my husband, and I — were taken to the regiment’s chief. He spoke to each of us individually and told us that Salekh and Ismail were allegedly the moderators of an opposition Telegram channel. They told us to keep quiet, not to go to human rights activists. They said if we told somebody, things would get worse — they would put us in jail — but otherwise, they might release us. To be honest, I didn’t even know those kinds of Telegram channels existed or what they say in them.

In the evening, they took the three of us home. Said’s feet were black from electric shocks. We didn’t know what to do: because of the quarantine in the republic, there was nowhere to go. They wouldn’t let us in [to see Ismail and Salekh]. I didn’t know what was happening to them. I was just horrified. I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t eat. Then we saw the video statement [with their apologies]. In the video, Salekh was in such a bad state that it scared me.

Two months later [after the arrests], [the authorities] called and told us to come in. They had all of the relatives of detainees gather in an auditorium. They said they had detained all of the opposition channel moderators and that they would release all of them if they agreed to cooperate.

Salekh and Ismail were released that same day. Their dad brought them home. It became clear that my sons had been beaten, tortured with electric shocks, and hit with pipes. But they talked about it superficially, they didn’t want to remember it. I know they tortured Salekh more, but he didn’t tell me about it, he didn’t want to.

[As for the Telegram channel], they told me it was just a place for them to joke, that it was interesting. I hadn’t known that my sons [had their own opinions about the Chechen government], but I wasn’t surprised. Because nobody’s happy with them. Everyone knows what they [Kadyrov's men] do, that they’ll snatch anyone.

‘I’d feel much better if they were far from Grozny’

The security forces told Ismail to work with them — to attract more people to a new [Telegram] channel. They offered him a salary. I immediately told him no, I don’t want you to. I don’t like this system and I didn’t want to give him up to it, and he didn’t want to either.

It was already clear to us that the authorities weren’t going to leave us alone. My sons decided to leave. Ismail reached out to human rights advocates from the Russian LGBT Network. A month later, we left Chechnya: Said and I were in one location, Ismail and Salekh were in another. My husband couldn’t go with us — his mother had suffered a stroke and couldn’t speak, so he couldn’t leave her alone.

It didn’t take me long to decide to leave, but it was a very tough decision. I’d spent 15 years building the home we lived in, and leaving it wasn’t easy. At that point, I thought I’d wait it out in [another part of] Russia and come back after Salekh and Ismail had left the country. I agreed with the kids — I wanted them to leave. I know it’s not easy to be a young person in Grozny. There’s no work there, no opportunities to do anything, to study. I would miss them, but I’d still feel much better if they were far away from Grozny.

We [Ismail, Salekh, and I] called each other every day on video and just talked, made jokes. February 4 [2021] was a normal day. I got up in the morning and made breakfast for me and Said. We ate breakfast and then went to the store. We were outside when Ismail called me and said the police had come to check his passport — supposedly, someone there had been robbed. Said got worried and told Ismail to call the human rights advocates because something was up.

An hour or so later, the authorities broke into Ismail and Salekh’s place, took their phones, and kidnapped them [they took them to Gudermes, a town not far from Grozny]. They also took my husband from our home [to the police station in Gudermes] and told him that our sons were there and that he needed to waive his right to a lawyer. The police spent the next four or five hours trying to convince him, scaring him, beating him. Finally, he agreed to waive it. He was in bad shape — he had just been released from the hospital that same day, he’d been sick with coronavirus for a month.

We found out [what Salekh and Ismail were being charged with] from the Internet and from the lawyers. It couldn’t be true! After they were released [and before we left], there was a very strict quarantine. You weren’t even allowed to leave your home without a pass. There were police officers standing and checking people’s documents at almost every intersection. It wasn’t like they [Salekh and Ismail] could just go out whenever they wanted.

The case against them was fabricated because [the authorities] wanted Ismail to help them. I don’t know why they singled him out. When we were home, they called him every day and told him, “Just say yes.” He told him he was still thinking [about it] because he didn’t want to make them mad. We left without agreeing to their conditions — that’s why they went after him.

Ismail Isayev

Zara Magamadova’s personal archive

[After Salekh and Ismail were kidnapped,] Said and I moved to a new apartment. Soon after that, we left Russia, and my husband followed suit. We were forced to leave. It wasn’t a question of whether I wanted to or not. To live in Grozny for so long and then to leave it all, move to a different city, then to a different country. It seemed so strange to me. But we did what we had to do. It didn’t make any sense to stay. If they [the authorities] had gotten ahold of us, it just would have made things worse for Salekh and Ismail.”

I’m not in touch with any of our relatives. My husband’s distant relatives have been pressured, detained, and forced to speak on camera. Of course, the authorities wanted to find out where we are so they could come and get us. They would have gotten us, too, but nobody knew [where we were].

‘No matter what, they’re my children’

I’m really lonely [where I am now]. But I don’t want to go home yet. I don’t know what will happen in the future — I need to think more about what to do. It’s peaceful here. I go to language classes at a school in the mornings. Other than that, I don’t really do much. The school at least provides some kind of distraction. When I really start feeling bad, I go out and walk through the streets.

The hardest part is thinking about them every day, worrying. I can’t sleep at night. I lie awake until two or three o’clock in the morning thinking about them, how they’re doing. I don’t know how I’m supposed to live like this. It’s very hard.

The only way I hear about my sons is through their lawyers. I know they’re in solitary confinement. The lawyers have tried to get the case transferred to another region of Russian. At least then there would be some hope of honesty, but the [Chechen] Supreme Court denied their request. [In December 2021,] Salekh and Ismail went on hunger strike. They kept it up for ten days. That whole time, I couldn’t eat either, I was so worried. But nobody went to check on them, nobody asked about it, so they ended the hunger strike.

I contacted [Russia’s Human Rights Commissioner Tatyana] Moskalkova. She gave me a formal response, but nothing changed. They were tortured in the pre-trial detention center, but nobody’s investigating it. The only thing I have left is hope — I’m hoping for the best.

If I’m honest, I never spoke with my sons about their sexual orientation. That’s just not something we talk about, especially with boys. I didn’t know anything. Now it’s not so important to me. I believe it’s important to fight for them regardless of who they love, what they’re interested in, or who they believe. I’m fighting for my sons, who were kidnapped and had a criminal case fabricated against them. I’m fighting for them because they’re innocent. No matter what, they’re my children. I’m on their side. I’ll support them through everything. I want them to be released — that’s all I care about.

Update. State prosecutors have asked for Salekh Magamadov and Ismail Isayev to be sentenced to 8.5 and 6.5 years in prison, respectively, the crisis group CK SOS told Meduza on February 11. Chechnya’s Achkoy-Martanovsky District Court is expected to deliver a verdict on Friday, February 18.

Interview by Kristina Safanova

Translation by Sam Breazeale

Rustam Borchashvili

Borchashvili was part of a group led by Aslan Byutukayev, who’s known as “Chechnya’s last field commander” ( In the mid-2000s, Byutukayev led a suicide squad that was involved in many high-profile terrorist attacks. According to official reports Byutukayev was killed in January 2021). Whether Borchashvili is still alive has not been confirmed independently. The Chechen authorities first reported that he had been killed in 2013. But Ramzan Kadyrov announced his “liquidation” on two separate occasions in 2020, as well. According to Novaya Gazeta Borchashvili is still on a federal wanted list.