Ukraine has ratified an international women's rights treaty that critics claim is ‘LGBT propaganda.’ Meduza explains.

1.

What happened?

2.

What is the Istanbul Convention?

3.

Is Ukraine just checking a box?

4.

Who opposed the ratification?

5.

What do the Convention’s authors mean by “gender?”

6.

What are critics’ arguments against the Convention?

7.

How have the Convention’s authors responded?

8.

Back to Ukraine. Why did they choose now to ratify the convention? Did the EU require it?

9.

What has been the outcome of the debates?

10.

How might the Convention’s ratification affect the war?

11.

What’s the Istanbul Convention's status in Russia?

What happened?

On June 20, Ukraine’s Parliament voted to ratify the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, better known as the Istanbul Convention. The following day, President Volodymyr Zelensky signed the bill into law.

The domestic campaign to get Ukraine's leaders to ratify the document, which they first signed back in 2011, lasted several years; supporters faced tough pushback from conservative politicians and the church. Some experts see the signing as a signal to the EU, which granted candidate status to Ukraine on June 24.

What is the Istanbul Convention?

The Istanbul Convention was signed in 2011 in Istanbul (hence its name). Its full text can be read here. So far, it’s been ratified by 34 of the Council of Europe’s 46 member countries.

Turkey, where the treaty was signed, withdrew from it in 2021, claiming it was being used as an instrument to “normalize homosexuality.” Poland had already done the same thing a year earlier, claiming that the convention was forcing schools to teach gender theory lessons rather than focusing on women’s rights. Both withdrawals were met with strong opposition from protesters, who continue to fight to get their countries to re-enter the treaty.

Is Ukraine just checking a box?

No — the document’s ratification has important practical consequences. Rather than just serving as a recommendation or a statement, the Istanbul Convention provides a clear road map for better protecting women’s rights. In fact, it may be the most effective international treaty to protect women’s rights ever created.

First, the treaty has led many European countries to criminalize sexual violence. The document clearly outlines the various types of gender-based violence: sexual violence, psychological violence, stalking, forced marriage, genital mutilation, forced abortion and sterilization, and sexual harassment. It also states that a community’s cultural characteristics — such as the tradition of “honor killings” — don’t count as an extenuating circumstance in cases of gender-based violence.

In addition, the Convention provides for the creation of special commissions to record cases of violence and exchange data, as well as infrastructure for preventing violence, treating victims, and working with abusers. Every country that ratifies the document is required to provide funding to support these goals, whether that means financing 24-hour hotlines or opening shelters.

Who opposed the ratification?

In short, the convention was opposed by a number of populist politicians and conservative organizations who together launched a full-fledged protest campaign. One of their main issues with the treaty is the use of the word “gender”; many of the document’s opponents in various countries paint it as “gender theory” propaganda that threatens to “destroy family values.”

In 2021, for example, the Constitutional Court of Bulgaria (which has not signed the Convention) declared the treaty unconstitutional. “Gender” has effectively become a bad word in the country; in televised political debates featuring Bulgarian Orthodox Church representatives, the phrase “gender theory” has been used as shorthand to accuse others of moral depravity.

The situation is reminiscent of Vladimir Putin’s mention of “so-called gender freedom” in a speech on March 16: the concept of “gender” in these cases is used without context and symbolizes an amorphous threat to “tradition.”

What do the Convention’s authors mean by “gender?”

In the Istanbul Convention, the word “gender” is defined as “the socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women and men.” This definition might be considered trans-inclusive, but it’s a far cry from the pro-gender-transitioning propaganda its critics claim it is.

Gender transitioning is the process of changing one's gender presentation or sex characteristics to align with one's internal sense of gender identity. It doesn’t necessarily entail making any physical changes to one’s body, and most of the time, any hormonal and surgical changes come only after a person has transitioned socially.

The document only requires countries to “undertake to include a gender perspective in the implementation and evaluation of the impact of the provisions of this Convention” — in other words, to take into account changing social realities.

What are critics’ arguments against the Convention?

Most often, they claim the Convention goes against local traditions.

Their favorite passage to cite is the following one:

Parties shall take, where appropriate, the necessary steps to include teaching material on issues such as equality between women and men, non-stereotyped gender roles, mutual respect, [and] non-violent conflict resolution.

Conservative politicians fear that this section would require schools to teach “gender theory.” In Poland, where the Episcopate and conservative politicians have pointed to that very passage, as well as in Hungary, homosexuality is often equated with pedophilia. This is just one component of a politics built on exploiting national trauma, something both countries share.

According to many Polish and Hungarian politicians, “LGBT” refers to an organized, foreign-funded movement that serves to undermine the foundations of the state, rather than regular people who belong to marginalized groups. Similar ideas abound in Russia.

Turkey’s decision to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention was widely criticized by human rights organizations, but President Recep Erdoğan’s press office responded that “the normalization of homosexual relationships goes against Turkish society’s social and family values.” Several months earlier, Erdogan said that the key to protecting women is to encourage morality and civil institutions.

How have the Convention’s authors responded?

Council of Europe representative Daniel Holtgen said in March 2021 that the treaty’s main priority is to protect women from violence.

The Council also prepared a press release title “Ending misconceptions about the Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence,” as well as a brochure with the answers to some frequently asked questinos.

Back to Ukraine. Why did they choose now to ratify the convention? Did the EU require it?

The EU isn’t the only relevant factor. First of all, it doesn’t require member countries to sign the convention, though it does require a commitment to democracy and human rights, and a willingness to defend women’s rights is an important component in that regard. The Council’s Secretary General, Marija Pejčinović Burić, has praised Ukraine for ratifying the document for this reason.

But in the years the debate over the Convention has been going on, a political consensus has developed with regard to the obligations it imposes.

What has been the outcome of the debates?

In recent years, even without the Istanbul Convention, Ukraine has passed several pieces of legislation aimed at combating gender-based violence. In 2017, when Russia decriminalized domestic violence, Ukraine passed a law called “On preventing and countering domestic violence.” Zelensky signed a similar order in 2020.

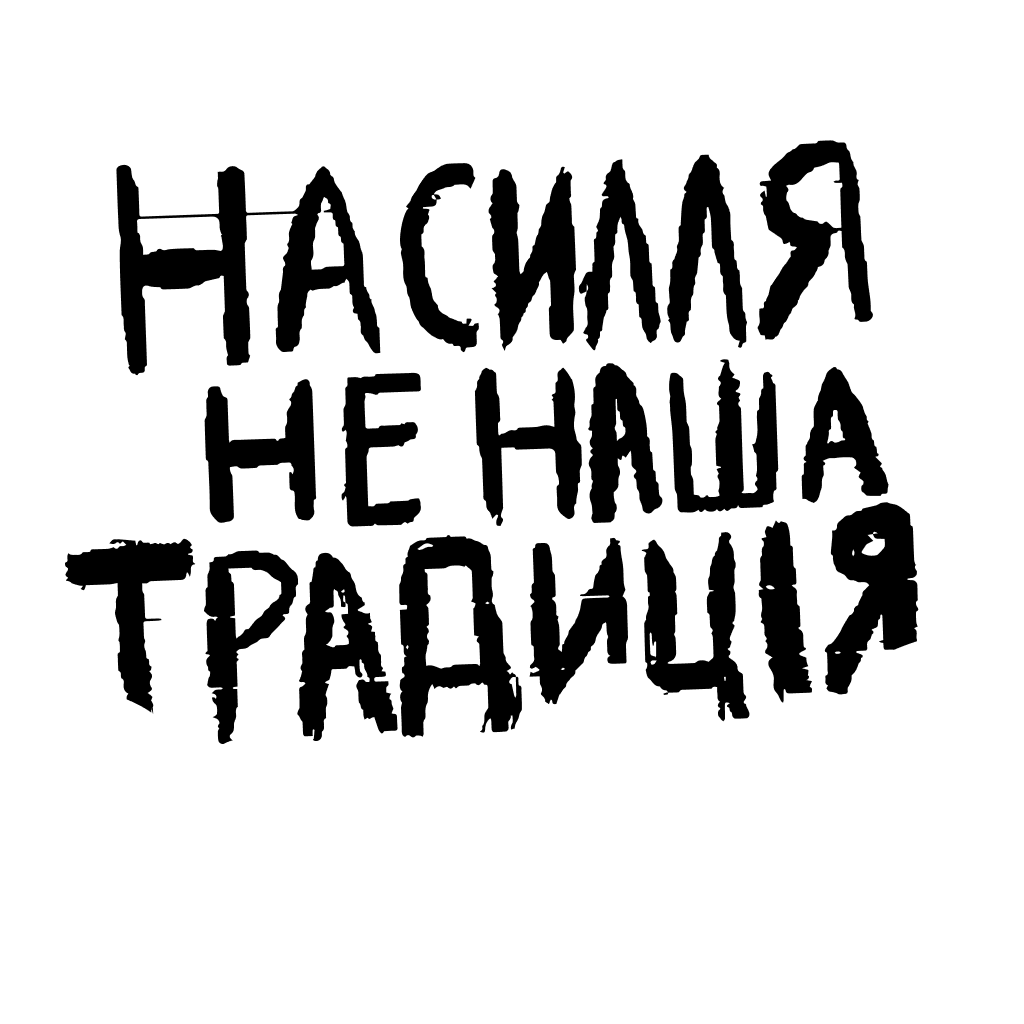

The fight to ratify the Istanbul Convention specifically was led by an organization called Women’s March. They put out two petitions — one in 2020 and another in 2021 — calling for Zelensky to ratify the Convention. In 2021, the activists held marches both offline and online in support of ratification; by then, they had Zelensky’s support.

“The ratification of the Istanbul Convention is a historic event for Ukraine. It demonstrates that we can be a society whose main values are humanism and human rights. We’ve been waiting for this decision for a long time,” Women’s March head Elena Shevchenko told Meduza.

How might the Convention’s ratification affect the war?

Unfortunately, the answer is simple. In the four months that Ukraine has been at war with Russia, there have been hundreds of recorded cases of sexual violence committed by Russian soldiers.

But in addition to sparking a surge of violence (both on the battlefield and in homes), the war has led to an embrace of traditional gender roles, an unsurprising consequence of society's militarization. The Istanbul Convention might serve to mitigate this process.

What’s the Istanbul Convention's status in Russia?

Russia was one of two European Council members (out of 47) that didn’t sign the treaty, so to say it’s far from ratifying it would be an understatement. The level of violence committed against women and queer people in Russia is extremely high.

In 2020, the Russian Interior Ministry refused to implement systems for surveying domestic violence victims expressly because the Istanbul Convention provides for such measures. When human rights advocates asked the agency about the decision not to sign the treaty, they received the following statement in response: “Due to the fact that the Convention requires lifting the ban on free gender orientation propaganda, Russia did not ratify it.”

Explainer by Anna Filippova

Abridged translation by Sam Breazeale